READ EXPERT BLOGS ON EMDR, PTSD, TRAUMA RECOVERY, SOMATIC THERAPY, EXPAT AND RELATIONSHIP SUPPORT—AVAILABLE IN LISBON, LONDON, AND ONLINE WORLDWIDE.

You Need to Feel Safe in Your Nervous System to Receive more Money.

We don’t just manifest from mindset—we manifest from our bodies. This piece explores how nervous system healing, EMDR, and somatic tools helped me feel safe enough to receive more money, joy, and stability—starting from the inside out.

First published in Elephant Journal July 2025.

("Yeah yeah, I’m a therapist, I already do." But… did I?)

I followed my soul’s calling — and it brought me to Lisbon with a newborn and a five-year-old.

After five years of dreaming about living abroad, I finally did it. I was five months pregnant when I decided I’d move to Lisbon. I planned to go in September — as soon as I could get a passport for my daughter. The urgency was simple: I didn’t want my five-year-old son to start school in the UK and then be uprooted three months later.

So, instead of the relaxed pregnancy you might imagine, mine was full of sorting flats, researching schools, designing a new website, shipping toys, and preparing for a career pivot. Nesting, yes — but with one foot already out of the country.

Two weeks after my baby was born, we were on the plane. “When will you rest?” people asked. “When I get to Lisbon,” I told them.

Spoiler: Lisbon wasn’t the rest I imagined.

In reality, it was the beginning of a solo-parenting whirlwind. My son had a tough adjustment to school. My baby screamed every time I put her down. I had a shiny new website and well-packaged services — and no clients. The biggest fear, day after day, was money. Would it run out?

Ten months later, I can see that of course my nervous system was dis-regulated. I was overwhelmed, sleep-deprived, anxious — and ashamed of how often I snapped.

But at the time, it didn’t register as “unsafe.” It just felt… familiar.

When constant stress is your normal

Growing up, I lived with a parent whose nervous system was chronically dis-regulated — due to their own unresolved intergenerational trauma. I walked on eggshells most of the time. I remember feeling deeply relaxed only when they weren’t home.

My grandfather once dragged me by the hair to the toilet because the toilet paper had run out. He said my sister and I were dirty pigs. That kind of nervous system imprint doesn’t just go away.

We piggyback off our parents’ nervous systems. When theirs is frazzled or frozen, ours doesn’t feel safe either — even if we can’t articulate that at the time. Our young amygdalas are always scanning: Is it safe to relax? Is it safe to be?

What is “dis-regulation,” anyway?

A dis-regulated nervous system is one that’s outside the Window of Tolerance — a term coined by Dr. Dan Siegel. This “window” is the zone where we feel grounded enough to process emotions, stay present, and make good decisions. Outside of it, we’re either in hyperarousal (fight, flight, panic, anger) or hypoarousal (shutdown, numbness, dissociation).

Children attune to their caregivers’ nervous systems. If our caregivers live outside the Window of Tolerance, we don’t just notice it — we absorb it.

And so, over time, not feeling safe becomes the new normal. We adapt.

I learned to cope by dissociating and controlling. I seemed calm to others — and in some ways, I was. But it was the stillness of hypervigilance, not peace. The kind of stillness where a deer freezes in the forest, hoping not to be seen.

And then Lisbon brought it all up.

Here’s the part I don’t want to skip — the part I believe matters most.

Looking back, I can see that the situation was divinely orchestrated. Call it God, Source, the Universe — whatever language you use. I believe I was being offered a chance to address something foundational.

It wasn’t just the practical stressors. The move, the money fear, the solo parenting — they were real. But what was being asked of me was deeper:

To address the part of me who still felt, every day, like the floor could give way at any moment.

That part didn’t need a strategy. She needed safety.

Yes, I looked at astrology — Mars was transiting my twelfth house, the house of the subconscious. That gave my inner controller a framework, a timeline. I pulled Tarot cards and knew I was in a Tower moment. But after the Tower? Comes the Star.

This was the work. And it was time to do it.

Even pain holds gold.

I believe the hard stuff holds treasure — if we’re willing to stay with it. Even when it’s horrible. Even when it feels like we’ll break.

Whatever comes up is here for a reason.

Because we can’t create abundance on a cracked foundation. We have to feel safe — not just think safe — in order to truly receive what we’re manifesting.

That’s why nervous system work is so powerful. It’s not “just” trauma healing — it’s foundation building. For the life, income, and creative vision you want to birth.

Nature first

Nature is proven to regulate the nervous system. Studies have shown that spending time in green spaces reduces cortisol levels, lowers heart rate, and activates the parasympathetic nervous system. According to research from the University of Michigan, just 20 minutes in nature can significantly lower stress hormones.

We went to Monsanto Park every weekend, walking among eucalyptus and pine. Afterward, I was more available to breathwork, music, even conversation. The forest reset me.

Connected breathing

I followed Dan Brulé’s work on breath — using his YouTube videos to do 3–4 sessions a week once the kids were in bed.

Brulé is a master of modern breathwork, known for blending ancient wisdom with neuroscience and deep spiritual awareness. His style is simple, intuitive, and powerful. Breathing this way activated my parasympathetic system — the rest-and-digest state — and allowed me to touch into the divine, into clarity, into quiet.

The “Voo” sound

When I felt panic or overwhelm rise, I used a simple tool from Polyvagal Theory (Stephen Porges): the “Voo” sound.

It’s exactly what it sounds like — a deep, slow “vooo.” The vibration stimulates the vagus nerve, which plays a central role in calming our bodies and signalling safety. I’d do it quietly, taking deep breaths and letting the sound ground me. (Not ideal in a shopping centre — but perfect at home.)

EMDR: Healing the unsafe child

I used EMDR to go deeper.

I brought to mind a specific memory — or reconstructed one — of my younger self feeling unsafe. I noticed the sensations, the emotion, and the belief: I’m unsafe.

Then I tapped bilaterally and followed where my mind and body led. Sometimes memories came. Sometimes nothing. I always remind clients: you can’t get this wrong.

Once the intensity settled, I did the re-do: inviting in nurturing, protective figures to intervene. A superhero. A social worker. A kind animal. I let them comfort her.

Then I installed a new belief: I am safe now.

I’m also working with: It’s safe to feel certain. Because back then, certainty felt dangerous. You had to stay on edge to be prepared. But I want certainty now. I want it to feel safe.

So how does this relate to money?

Completely.

Most of us want money not just for things — but for the feeling it brings. Safety. Freedom. Certainty.

But here’s the paradox: we can’t manifest those things unless we already feel them internally.

The more I create internal safety, the more external security mirrors it back. My income reflects my regulation. My opportunities match my capacity to receive.

If you want to increase your income beyond what’s “normal” for your family, culture, or past — your nervous system needs to feel safe doing that. Otherwise, the body will sabotage it.

Beliefs like:

- “If I get rich, I won’t belong.”

- “They’ll resent me.”

- “I’ll be judged.”

…live in the body, not just the mind. And they need somatic attention.

This is sacred work. And you don’t have to do it alone.

A daily practice of creating deep safety is the most powerful abundance work I know.

So, dear reader — may you feel deeply secure within. May your foundation feel strong enough to hold everything you desire.

And may you feel safe to receive all the abundance you wish for.

Why Struggling Feels Safer than Manifesting Abundance.

Why does ease feel dangerous when we’re trying to manifest abundance? This deeply personal story explores how trauma and inherited survival patterns can block us from receiving—and how EMDR, nervous system work, and radical self-compassion can open the door to lasting change.

First published in Elephant Journal, June 2025.

The Grief Beneath the Surface

Dear part that feels so crushed and sad,

I want you to know that I see you. I am now aware this is what you crave most of all: to have your feelings seen and validated.

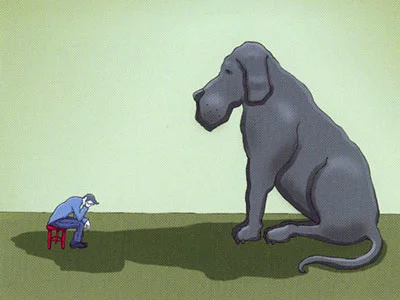

I imagine you as a young, small girl sitting on a dark shore, looking back at a wild grey-black ocean under heavy storm clouds. This is the aftermath—and you are grieving the parts of yourself you had to cut off in order to get to the shore. In order to survive.

The sensitive parts. The parts that feel things deeply, intensely, passionately.

It wasn’t possible to survive the ongoing situation with them intact, so you amputated them and fled.

You survived.

But now you feel defeated.

Crushed. Almost dead.

You can’t anymore. You can’t take anymore. You can’t do anything anymore.

You feel overstuffed—holding the emotions of others.

You feel overwhelmed with anxiety that no one is helping you hold.

You feel crushed and defeated by the constant struggle.

You have no more fight.

You feel like you have nothing left to give.

You are so bl**dy tired.

But what upsets you most isn’t even that. It’s what happened to you.

The parts you had to cut off.

And the fact that you had to do all of this alone—without your pain being seen, witnessed, or stopped.

Even worse, that I haven’t seen you either. That I’ve been doing the same thing to you—when what you’ve needed most is for me to notice.

When Art Activates the Wound

As I said this to my part, something shifted. I felt a flicker of energy, of hope. She felt heard. I was doing something right.

She had been triggered during a rehearsal. I was playing a woman grieving infertility, exhausted by her struggle through IVF. The material from The Quiet House stirred my own grief, my own weariness.

Later, while doing abundance manifesting work on negative core beliefs, that same part surfaced again. This time, the pieces started coming together.

I found clarity.

I found the belief that had been running the show.

The Realisation: Manifesting Isn’t About Calling In—It’s About Making Space

A journal prompt had asked: What would you do if you received everything you wanted?

For me, abundance meant freedom and safety.

But the freedom to do what?

I realised: the freedom to play.

To play through acting.

To play with my children.

And that’s when the guilt came.

The criticism.

The self-judgement.

As I followed the thread, I uncovered a core belief:

That I must struggle and suffer in order to be safe and connected.

The Root: The Hidden Contract

It made sense.

I was the eldest daughter of a solo parent of two, navigating the waves of inherited trauma and chronic dysregulation.

Without realising it, I had made a silent vow:

I will carry your struggle and suffering if it means I can stay connected to you.

The illusion was that this contract guaranteed safety.

It didn’t.

But as a child, my nervous system was wired to seek closeness at any cost.

This was the fawn response in action: the hope that if I attuned to her pain, I could keep myself safe.

What I internalised was this:

Abundance, ease, and visibility = danger, guilt, and loss.

The Broken Record: Living Half-In

That belief became a loop.

Even after relocating to Lisbon, returning to acting, and following my creative path, I couldn’t fully step into the life I’d created. One foot remained in survival.

Sure, part of it was the natural adjustment to a big life change. But there was more.

A deeper resistance.

A belief that ease was unsafe.

Even though I was working hard to shift things, a powerless part of me quietly sabotaged the process.

For example: I didn’t consider promoting my therapy services locally. I was so focused on working with actors that it didn’t even occur to me. But when I finally did, clients came.

I saw then that I didn’t need to let go of being a therapist.

My calling was always to midwife creativity—to bring what’s hidden into the light.

We are all artists of our own lives.

And I’d been midwifing my own process all along.

Healing Through the Body: EMDR as a Portal

That small crushed part was carrying the full weight of my struggle wound.

Her loyalty to suffering had nearly broken her.

But when I witnessed her, when I validated her, and when I named the belief, something shifted again.

As an EMDR therapist, I offered her a rescue.

With bilateral tapping, I invited her story to unfold.

I imagined safe people intervening.

A rainbow dragon, a kind social worker—whatever she needed.

That’s the magic of EMDR. You get to rewrite the story.

And then I anchored a new belief:

“I am safe, worthy, and lovable in my ease, joy, and abundance.”

Rewiring the Brain: A New Belief System

That’s neuroplasticity.

The more we imagine ourselves safe in joy, the more our nervous system learns that it’s true.

These shifts take time—but they’re real. And I felt it.

Soon after, I began to receive more aligned clients.

The external began to shift as my internal world softened.

When the Breakdown Is the Breakthrough

I had heard over and over that what you want to manifest is already inside you.

But I didn’t believe it could be that simple.

And that?

That disbelief was the struggle wound speaking.

I didn’t realise that the emotional breakdown was the breakthrough.

That the messiness was a sign that something beautiful was trying to land.

In Tarot, it’s the Tower card before the Star.

Destruction before illumination.

Manifesting isn’t about forcing things to appear.

It’s about making space—by going inward, by feeling what’s real, by meeting the parts of us that were left behind.

So I ask you, dear reader:

What is right in front of your nose right now?

When you think about what you’re trying to manifest, how are you feeling—right now?

Or what are the most dominant negative feelings and emotional states showing up lately?

How do they connect with your deeper story—and with what you’re longing to call in?

Being Authentic is Your Portal

For all the programmes and ideas I’d developed, I couldn’t feel grounded in any of them.

I didn’t know how to access my own abundance.

Until I saw: it had been there the whole time.

Becoming the artist of my own life.

Sharing my story.

Midwifing my own creative process.

That was the portal.

The Wound & the Way

As a therapist and actress, I see now how common this wound is.

This struggle wound.

This inherited survival contract.

The guilt and shame at the idea of experiencing ease.

The tug-of-war between wanting to shine—and wanting to hide.

It’s hard for anyone to carry this.

But especially for those of us who long to express ourselves creatively.

And paradoxically, I think it’s the unseen child within us who wants that shine. Who wants to be witnessed and known.

So if something here resonates, I hope it offers a small light for your own path.

Because abundance doesn’t come from pushing harder.

It comes from being real.

From feeling everything.

From midwifing your own transformation.

Which—you don’t have to do alone, by the way.

And then?

You magnetise.

So dear reader, may you believe you are safe, worthy, and lovable in your ease, abundance, and joy.

I Tried to Manifest My Dream Life—& Here’s What Finally Started to Work.

In my own work (and with clients), I use a mix of EMDR, IFS (parts work), and somatic tracking to work with these protective layers.

Once I notice a part—say, the one that wants me to stay small—I start relating to it:

- What does it fear would happen if I changed?

- What is it protecting me from?

- What did it need, back then, that it didn’t get?

Often, these parts are holding buried emotions like rage, grief, or fear. They’re not trying to block us. They’re trying to keep us safe.

Sometimes I dialogue with them. Sometimes I just sit with them. I let them express. I tap (left–right–left–right, like in EMDR). I remind them that now is different. That we are safe.

This isn’t about pushing through.

It’s about integration.

First published in Elephant Journal, June 2025

I want to share my experience of trying to manifest a new life—and what I’ve learned about why it wasn’t working the way I thought it would.

The Invisible Force Holding Me Back

About two and a half years ago, I found myself in a kind of emotional fog. I wasn’t exactly depressed, but everything felt flat. Bleak. I was looking at the next 20 years of my life—doing the same trauma therapy work, in the same neighborhood, in the same rhythm—and I just couldn’t. My soul felt numb. There was nothing particularly wrong, but the idea of continuing as I was left me cold.

And so I asked myself: What brought me joy when I was younger?

The answer came quickly—acting. That creative fire, the embodied joy, the freedom of expression. I started weekly online acting classes. It woke something up in me. It helped me listen more closely to my soul’s voice.

A year and a half later, I moved to Lisbon. With a five-year-old. And a newborn. And no support system.

At the same time, I began shifting from purely trauma therapy to working with creatives and exploring the acting world for myself. It was a massive change—not just of place and career, but of identity. And while my soul knew I was doing the right thing… the rest of me? Not so much.

Practice One: Visualisation with Shadow Tracking

That’s when it started: the internal resistance. The part of me that didn’t believe it was safe to expand. That didn’t believe I could be supported. That didn’t believe I was worthy.

Even though I’d already done seven years of therapy—and trained as a trauma therapist myself—these old beliefs came roaring back. Not in obvious ways. But in the background. Sabotaging. Shaping my decisions. Tightening me up with fear.

I threw myself into manifestation work. Visualisations. Affirmations. Vision boards. I followed the big names—Amanda Frances, Lenka Lutonska. I wanted to believe it would work. I tried to feel the feelings of abundance, success, joy.

But I couldn’t.

I couldn’t access the feelings.

I couldn’t hold the vision.

I just… went numb.

That numbness wasn’t new. I’d met it before in my acting training, in feedback from people who couldn’t “read” what I was feeling. As a therapist, I know what that is: a protector part. One that came along early in life to shield me from unbearable emotion.

So I did the work. Again. And I realised something that changed everything:

You can’t manifest your dream life if your nervous system doesn’t believe it’s safe to have it.

Practice Two: Befriending the Parts That Hold You Back

One of the most helpful things I started doing was pairing visualisation with awareness of what comes up—especially the parts of me that resist.

Try this:

- Take five minutes to fully visualise the life you want. Let it be detailed. Specific. You having the money. The time. The love. The ease.

- And then… just notice what comes up.

- Numbness?

- Guilt?

- Grief?

- Resistance?

- Self-doubt?

For me, it was grief. A wave of it. A part of me that remembered not getting what I needed as a child. A part that believed it was too late now. That it wasn’t safe to hope.

If something like this arises, don’t bypass it. Be curious. Ask:

- “What belief is underneath this?”

- “When did I first feel this way?”

- “What part of me is carrying this?”

This process alone can reveal so much.

Practice Three: Releasing Through the Body

In my own work (and with clients), I use a mix of EMDR, IFS (parts work), and somatic tracking to work with these protective layers.

Once I notice a part—say, the one that wants me to stay small—I start relating to it:

- What does it fear would happen if I changed?

- What is it protecting me from?

- What did it need, back then, that it didn’t get?

Often, these parts are holding buried emotions like rage, grief, or fear. They’re not trying to block us. They’re trying to keep us safe.

Sometimes I dialogue with them. Sometimes I just sit with them. I let them express. I tap (left–right–left–right, like in EMDR). I remind them that now is different. That we are safe.

This isn’t about pushing through.

It’s about integration.

This Is Not a Quick Fix

Thoughts alone can’t move trauma.

Emotions need to be felt.

Bodies need to be involved.

If a wave of emotion comes—rage, grief, fear—I let it peak and crash like a wave. I tap. I breathe. I allow it to rise and fall, rather than shut it down.

Here’s one way I do this:

- I lie down and do connected breathing.

- I breathe into the part of my body where I feel blocked (for me, it’s often my lower or upper back).

- I stay with the breath.

- I let the emotion move.

- Sometimes I cry. Sometimes I want to punch pillows. Sometimes I shake.

That’s all okay.

Because after that wave passes, I can finally access the positive belief I’ve been trying to install:

- I am safe.

- I am worthy.

- I am powerful.

- I don’t need to struggle.

- It’s safe to receive.

You can only truly believe those things when your body believes them too.

I want to be real: this isn’t a “five minutes a day and your dream life arrives” kind of thing.

For those of us with attachment trauma, it can take 6–12 months of steady, committed work to create real change. But it can happen. I know because it’s happening for me. Bit by bit. Day by day.

I’m not sharing this to sell you anything.

I’m sharing it because it’s what I needed to read.

It’s what I wish someone had told me when I felt like I was doing everything “right” but still getting nowhere.

You’re not doing it wrong.

You’re not broken.

You just need a deeper approach.

And if you don’t want to do it alone—you don’t have to.

Thanks for reading my story.

And if it helped you even a little… I’m really glad.

8 Radical Tips to Save your Relationship or Help you Find (& Keep) your Soul Mate.

Relationship questions are never black and white. Any security derived from judging the other quickly is an illusion to avoid normal feelings of insecurity when getting closer to someone. And that insecurity will stick with you into the next and next relationship like a fly to a piece of shit.

Edited and first published by Elephant Journal.

The young woman sat on the worn suede sofa in her living room, alone. It was a hot Summer’s night. Her legs tucked under her, she wore a white cotton mini skirt and a dusty pink camisole top. She ran her fingers through her shoulder length highlighted hair and downed her glass of Prosecco whilst sighing deeply. Blue Kohl was smudged faintly beneath her brown eyes, washed away by tears. “If only I’d been a bit more patient with Rick”, she thought. “If only I hadn’t over-reacted to some of his antics. We had a good thing and by getting as nervy as an Ascot race horse each time he said or did something I didn’t like, I’ve ruined something that could’ve turned into the real deal…….”

Sound familiar? Here are the mindset changes needed to either:

Save your relationship or find (and keep) your soulmate

1) Know that certainty is an illusion

Having relationship problems? Don’t decide one way or the other or move on too quickly. I’m not suggesting that we allow our boundaries to be trampled all over like the field at Glastonbury. But, in this individualist capitalist culture of hyper-consumerism which includes swiping right, summoning dinner to our doorstep within minutes, buying cheap clothes to return as quickly as they arrive, the implicit message we get is “judge quickly and move on fast if the ‘fit’ is not quite right”.

‘Is Your Date a Narcissist?”, ‘How to handle an Avoidant Partner” or, “10 Ways to Know if He is The Person for You’ are headlines I read when scrolling through relationship blogs on social media. Of course, it’s very important to be aware of potentially harmful individuals, however in the current socio-cultural context there is a huge need to label everything and everyone. And it’s not necessarily helpful.

As a Gestalt therapist, I am wary of labelling. Gestalt Therapy asserts that ‘the self’ is a process which is constantly re-creating. To diagnose is to objectify ‘the self’. In some cases, a diagnosis can be helpful however I suspect that labelling our partner as a narcissist, an avoidant or ‘fucked up beyond repair’ helps us feel temporarily more secure and nothing more. We get a convenient reason to leave or blame or feel superior because our partner is ‘wrong’, not us.

Bullshit!

Relationship questions are never black and white. Any security derived from judging the other quickly is an illusion to avoid normal feelings of insecurity when getting closer to someone. And that insecurity will stick with you into the next and next relationship like a fly to a piece of shit.

2) Think, “how can I practice my relationship skills NOW whatever my current situation?

Flabby relationship muscles are like the gut of a cat that’s had eight litters of kittens. We get these when we label individuals too quickly and avoid commitment. After the initial 3-month honeymoon period is over, it’s usual for the rose-tinted glasses to fall off and the quarrels to start. Some of us want to leave, more of us wish our partner was different and try to change them. Others try and ‘fix’ ourselves to put up with their flaws. Neither of these solutions are helpful. If we keep on leaving when the going gets tough, then we’ll keep on leaving till we don’t have enough strength to lift our Zimmer frame through the doorway.

‘They’ become the problem when we focus on how ‘narcissistic, ‘avoidant’, or depressive they are, and refuse to see how we are also contributing to the problem. I’m not saying we should stay in a relationship where we mostly feel unsafe or unhappy. But the fact is that EVERY SINGLE PERSON WE DATE WILL HURT US AND DISAPPOINT US at some point. That’s because we’re all flawed human beings. If things are really bad, then we should absolutely leave the situation. But if we are not leaving because we ‘love them’ or because we hope things can improve, or because the good still outweighs the bad, then we are at least partly responsible for the dynamic because we are choosing to stay.

3) Find compassion for their ‘issues’

Dis-identify from their ‘stuff’. We can bet that if someone has commitment issues, communication issues, anger issues or whatever other ‘issues’, they had them long before we came along. Therefore, their issues are NOT A REFLECTION OF OUR WORTH, and we do not need to over-react to them. If we do, then that is our issue! If they don’t call when they said they would, if they forget our birthday, if they say they are too tired/depressed/anxious to join us at our best friend’s party, it’s not because we are ‘not good enough’, ‘unworthy’, ‘too fat’, or whatever other bullshit our critical voice is throwing at us.

Let’s see instead if we can find some compassion for their struggle. After all, if this was our best friend, wouldn’t we show empathy and understanding? Why is it that we lose that compassion and empathy when it comes to our partners?

We can still communicate our hurt, our annoyance etc. but we don’t start screaming, shouting, swearing, threatening, blanking, avoiding or any other type of reactive behaviour.

When we muster up that compassion, and I’m not saying it’s easy but try imagining that they’re your best friend, we disconnect from their ‘stuff’ and no longer allow it to trigger own ‘stuff’.

The magical bonus of extending compassion towards our partner is that we start to develop that same empathy towards ourselves.

4) Regulate your emotions

If we take offence because our date didn’t call for four days, it’s because our own stuff about being abandoned is triggered. We start to obsess, our mind runs catastrophic movies about them in bed with someone else. We react disproportionately to the current situation since they are only a love interest at this time, even if we’ve fantasised them into a future husband.

So, we have a choice here. We can practice behaving differently and soothe the part of us that’s terrified of being abandoned. We can imagine the young girl who was rejected by a parent and imagine surrounding her with love and care. We can visualise an alternative, ideal parent who provides constant and secure love. We can incorporate some bilateral tapping during this process. This is a technique taken from EMDR which helps to ‘install’ a new experience to overwrite the unhappy abandonment script.

We can sit with our feelings of anguish or fear whenever they arise. This is what Tara Brach teaches in her RAIN technique. We notice the distress in the body and feel it without doing anything about it. We observe the feelings intensify and then ebb away. We realise that they aren’t going to overwhelm us or plunge us into an abyss of despair, that we can bear them and that they don’t last forever.

5) Challenge your thoughts and assumptions

We can use our current relationship/dating distress to challenge our catastrophic and thinking and tendency to make assumptions about the other without bothering to reality check them. We monitor our thoughts and notice when we’re imaging the worst. We ask, what is the concrete evidence for that thought? When we find ourselves assuming they’ve gone off us, we think of other reasons they may not be texting which have nothing to do with us for example they feel tired, depressed, or anxious we’ve gone off them, for example.

Running movies about the other person’s behaviour whips up anxiety and anguish quicker than a Vitamix blender whizzing up a banana smoothie. We end up pushing the other person away which is exactly what we’re most scared of.

Thinking differently is a win-win. Regardless of the relationship outcome, we’ve honed a new skill, we’ve added a new tool to our collection of relationship building tools. Either we will transform this relationship, or we’ll feel more confident heading into the next one with a smaller car crash of relationship fuck-ups behind us.

6) Express yourself transparently without judging, accusing or threatening.

Being transparent is crucial. We can’t expect the other person to ‘mind-read’ us and know what we need and want as if they were our parent (and even parents don’t always do a great job of that). How can we expect to be fulfilled in our current relationship if we don’t communicate what’s really going on for us? So often in my own personal therapy and as a therapist to my clients, transparency comes up. I ask, ‘have you told him that you feel hurt by his behaviour?” Or, “have you told her you feel anxious when she doesn’t call? Often, we shame ourselves for our vulnerabilities and stop ourselves expressing them. There is nothing shameful about yearning for someone or feeling insecure about someone. These are human experiences. If we don’t express them then we tend to blame, accuse, criticise and threaten instead. We try to manipulate the other and this always backfires. If I tell you I’m going to dump you because you don’t seem interested in me then you will probably feel threatened and retaliate with something like, ‘go on then, if that’s what you want’. I end up alone when that’s really not what I wanted. Actually, if I’d communicated the whole of my experience I would have said something like, ‘when I don’t hear from you I start to imagine that you’re no longer interested in me and I feel sad and anxious’. This language is more likely to soften the other person and leaves an opening for them to respond without getting defensive.

It’s the usual stuff about making “I” statements and owning our experience without making accusations. So, we make ourselves a bit vulnerable, what’s the worst that can happen? We’re no longer a child under ten who can’t protect themselves. The world will not end, and we will not die by being honest about ourselves. Actually, by expressing our true inner experience we feel empowered because we’ve just honoured and validated ourselves, regardless of how the other responds.

7) Practice setting healthy boundaries

Any relationship, whether we sail off into the sunset or capsize dramatically, is a great practice ground for setting boundaries. In order to set boundaries, we have to know what we need. Boundaries signal what is negotiable and what is non—negotiable. This is a great question to consider because so many of us, myself included, ignore our needs as if they were extra toppings at the ice cream parlour, indulgent but not necessary. Getting our needs met is fundamental in order to keep on going without having a breakdown.

In our current relationship we can start to evaluate whether our partner’s behaviour encroaches on our needs, or whether we can bend a little like a willow tree rather than being as rigid as a toddler having a tantrum. When they forget our birthday we can ask, do I need them to remember? It sure as hell would be nice but I don’t need them to remember my birthday in order to keep on thriving. Nor do I need to react by sending a flurry of nasty texts or ignoring them for two days to punish them. I can decide to be curious about their reason for forgetting and at the same time express my hurt and disappointment.

On the other hand, do I need to be in a relationship with someone who is honest? Yes, I do otherwise I find it difficult to trust. If I find out they are lying three months after we’ve been officially in a relationship (as opposed to dating when a few half-truths are not uncommon) I’d seriously consider ending our liaison.

When we get really clear on our needs and express them, then we can choose which behaviours we’re going to make a big deal out of and which ones we are going to be more flexible about. I’m not saying we just accept that our birthday has been forgotten. We express our feelings and we try to understand why they forgot, but we don’t overreact. That invariably backfires and leads to more ‘forgotten’ birthdays, other passive aggressive behaviour or no one around to forget our birthday the year after.

8) Learn to be ok with difference

Differences are the most difficult relationship issues to manage. For example, we expect to chat to our love interest on a daily basis and feel disappointed and hurt when we only hear from them every few days. Or, we are tee total and they like to get dead drunk every weekend. We might cajole them into doing what we want. When that doesn’t work we try to manipulate them into it by promising something in return. If that doesn’t work and the stakes are high like wanting different holiday destinations, we try to force them into choosing what we want. This ends with our partner agreeing but secretly teeming with resentment that shows up in passive aggressive ways like losing their libido, being on their phone when in our company, coming home later from work. Or it can lead to a blow-up argument and stale-mate or we ‘give in’ but punish our partner with a wall of silence, ‘losing’ our libido or other stroppy behaviour. We cannot accept that our partner is just different from us. Their difference does not make them worse than us nor are we superior because of our choices. There isn’t necessarily anything to do but be curious about their difference and understand and appreciate them more for the unique human being they are. Hopefully in turn they will appreciate our differences. We can also ask ourselves whether the disagreement is about a need of ours. Going on holiday with our partner may be wonderful but is it necessary? Is it worth potentially throwing the relationship away for that?

If we are willing to try these practices, and they aren’t easy, we might come to find that our hasty judgement of our partner was inaccurate and that they are a lot more complex and interesting than we thought. We’ll gain freshly honed relationship skills to transform our relationship without any need for couples counselling. And if things don’t work out, we’ll feel more confident going into our next relationship. Regardless of how good a fit the next person is, no relationship is protected from shoddy behaviour so better start upping your game now, with this one.

If you’d like some professional help putting any of the above tips into practice, I’m happy to chat with you about how we could work together.

7 Reasons why we Haven’t found Real-Ass, Committed, Healthy Love.

But when a date or a relationship goes wrong, we don’t dare ask for feedback. If our date tells us they don’t want to continue seeing us, our inner critic attacks us like a wrinkly-headed vulture about to gobble up a tasty dead lion. “It’s because you’re too fat, too ugly, too unlovable, because they spotted that there is something truly wrong with you”. How is it that we rarely challenge this vulture by finding out why they don’t want to see us anymore? More than likely it is because of them rather than us. A recent client of mine, after taking the risk of asking, found out it was because their date was looking for hook-ups and polyamory whilst they were looking for monogamy.

“There's something wrong with me”, my client says, “inherently wrong with me. Everyone else is hooking up, settling down or having children. I'm being left on the fence, passed by. I don't know why. Perhaps I'm too ugly, or too boring, or too closed. I've always felt left out, I must have been born this way... and will probably die this way too”.

So not true!

1. You have adopted some untrue and unhelpful self-beliefs

You were not marked out as a pariah at birth - How is it actually possible that there is something so fundamentally wrong with us that it marks us out, sets us apart from all other human beings as if we were some kind of pariah?

When my clients say this, I ask them what the specific concrete evidence is which backs up this idea that they are so uniquely unworthy compared to all the other thousands who are currently dating. If we think we are ugly we might ask, ‘in whose eyes?” In comparison to celebrities who are made up and airbrushed to the hilt? Or are we comparing ourselves to a particular societal norm? If so, which societal norm would that be? The Western world, Asian societies, African societies? And what is the societal norm in any of these? For example, in the UK would we say that black models, mixed-race, blonde or red-headed models feature most in magazines?

I don’t think that anyone would agree on what constitutes beauty or even whether the ‘norm’ is the most beautiful. Just think of how varied models look now compared to even 10 years ago.

And if that doesn’t help challenge our beliefs, we can do a reality check with our peer group. We can join a personal development group and realise how many of us feel the same. Perhaps we can risk telling a close friend that we doubt how we look and think it is the reason why we can’t find a date or a fulfilling relationship. I’m pretty sure they would also confess to some insecurities about their looks and I’m also pretty sure they would reassure us on our looks. If our critical voice continues to doubt what they say, we can reality check with more and more friends until there is firm evidence that, even if we are not text book looking, we are attractive.

Lastly, we can look at the evidence of what others are attracted to. Let’s think of our friends in happy relationships. Do we hold them to the high aesthetic standards that we hold ourselves? I’m pretty sure I speak for all of us by saying we don’t. I’m also struck by how the way we can speak to and judge ourselves is so diametrically different from the compassion and understanding we have for our friends. They are allowed to have the blemishes, curves and ungroomed nails that we do not allow ourselves, and yet we find them attractive as people. Why do we find them attractive? Because we see them as a whole, as a 3D living person complete with personality, attractive qualities and the ‘je ne sais quoi’that makes them the unique person they are.

Yet when we look at ourselves, we cannot get this perspective. We look at a 2-D selfie taken after a draining day at the office, and imagine we look like this all the time. Or, we see our side profile in the harshly neon-lit fitting room mirror of John Lewis, our buttocks over-emphasised in a mirror that isn’t properly fitted. Our heart drops and we feel depressed. But this is not a true representation of us. We are a moving, 3-D picture. And just as Gestalt psychologists stated, ‘the whole is greater than the parts’.

But I’m unworthy, people just ‘see’ me that in me, especially if they get to know me…

If we believe this, then we can ask ourselves, what is it specifically and concretely that we have done which supports the belief we are unworthy. Whenever I ask clients they respond with vague reasons such as, ‘I don’t know exactly’, or, ‘just because’. The reason for the vagueness is that these questions really nail their critical voice and reveal it as a fraud, just like a suitor whose been called out on a lie and they know their time is up. Only problem is, unlike the suitor who runs for the hills, our inner bully stubbornly holds on and refuses to let go.

We need to dig deep, really take a pick axe to that mother fucker. We can start by thinking of individuals we do consider to be unworthy. Would that be child molesters, murderers, granny bashers? And how do we compare to them? Surely, we would quickly agree that if 10 is unworthy and 1 is not at all and they are a 10 then we are a good 4, 3 or lower. Not unworthy then.

2. You believe the fantasy about everyone else's perfect lives and relationships…

The fact is that there is no such thing as a perfect relationship. Even very good relationships are rare. People meet, stay together and break up all the time. Just because your friends seem loved up now, does not mean that the relationship has long-term staying power or that it is fulfilling once the initial fantasy chemical driven part is over.

In my experience of counselling many couples, the initial attraction and the reason for staying together is that our neuroses fit.Which can be fine but generally where we are neurotic there is a younger, childish part present. So perhaps this part of us stays with our partner who is at times domineering or sarcastic or stone walls us because in other ways they make us feel ‘safe’. We put up with the bad because we don't know any different, maybe we experienced the same with our parents as children. The problem is, safe doesn’t equal interesting or stimulating. Perhaps our relationship is given the badge of social approval because it is steady and long-term, but is it healthy and happy? Hmm...

I don't mean to come across as a party pooper, or the voice of doom and gloom about relationships. Of course, it is very possible to have a fulfilling long-term relationship, I’m just saying don’t let your critical voice fool you into believing that everyone else is enjoying a fairy-tale romance, complete with popcorn and coke, whilst you’ve been left on the side.

3. You are not actually open to a relationship

I remember my own therapist pulling me up on this a while back. As I thought about my work schedule, it dawned on me that he was right. If I work anti-social hours when end at 9pm at night in the weekdays and if I fill my Saturdays with yoga and meeting friends, what amount of spare time do I actually have to give a relationship? Whilst a once a week date might be fine in the early stages, a partner might not feel satisfied with getting just the dregs of me on Sunday when Monday blues is already setting in.

How much energy do we have for someone else? By that I mean the energy to listen to them patiently when they are telling us about the struggles of their day. The energy to be fully present for them, to show up for them, to love them and to show them that love through actually being available for them. Can we honestly say we have this or do we find ourselves drifting off and wishing they would just leave us alone to watch Netflix? After all, weren’t these the qualities we wished for in another? When we look at ourselves honestly can we say for sure we are truly available, to meet someone else?

4. You give up on dating and relationships at the first hurdle

I’ve done that very thing before. A few bad dates and I throw in the towel and say, ‘that’s it, it’s not for me’.Only to sheepishly re-install my dating apps a month later.

Let me ask you, would you give up so quickly when trying for a major professional, educational or savings goal for example? Probably not. How is that we can be a lot more resilient about those goals, which may take years to attain, but not when it comes to our relationship goal? How is that when we take a knock professionally or at college, we ask for feedback and performance reviews and try to learn from our mistakes, even if our ego is a little crushed.

But when a date or a relationship goes wrong, we don’t dare ask for feedback. If our date tells us they don’t want to continue seeing us, our inner critic attacks us like a wrinkly-headed vulture about to gobble up a tasty dead lion. “It’s because you’re too fat, too ugly, too unlovable, because they spotted that there is something truly wrong with you”. How is that we rarely challenge this vulture by finding out why they don’t want to see us anymore? More than likely it is because of them rather than us. A recent client of mine, after taking the risk of asking, found out it was because their date was looking for hook-ups and polyamory whilst they were looking for monogamy.

How do we know our date didn’t get scared off by our fabulousness, or realised they were still in love with their ex? Absolutely nothing to do with us. And even if it is because they decide we aren’t their type? So what? Not everyone likes bananas or apples. If someone prefers bananas over apples, does that make apples unworthy? Of course not! I say as I crunch into my Pink Lady.

How about we view dating as a journey, as an interesting experiment we have set ourselves? Perhaps it will take three years to meet the right partner. And we learn from each date and person along the way, we hone our insight, streamline and finesse our requirements so that when we do meet the right person, we can be proud of the knowledge and prowess we have acquired.

5. You don’t’ actually go out and meet people

This might seem obvious but if we keep on doing the same things we always do and don’t meet new people, then perhaps it is time to do something new. I mean, prince or princess charming isn’t going to appear at our grubby bedroom window sill at night, wave their wand and fall instantly in love with us. If our routine consists of going to work, going home, hanging out with friends who are in relationships, married or with children, and at the weekend or going to the gym where no one talks to each other, the odds are we won’t meet anyone new.

Our inner critic can then use this as evidence that we are ‘unlovable’ and that we don’t belong. A judge would throw this evidence out in court. Just as getting a job can mean sending off piles of CVs and doing several interviews, finding a good relationship means putting ourselves out there. Whether that be through online dating and actually going on dates, or finding a fun activity to try that we’ve always been interested in. Maybe acting classes, improv classes, rock climbing, joining a hiking group etc. Ideally, it’s something we will enjoy anyway so finding a date is just a bonus.

6. You don’t choose the right people to date

Rather than focussing on why you are not good enough, have you thought about why past partners haven't been good enough? Looking back on past relationships I’ve had, I realise that I was making some overly big compromises without really realising it. The partner who keeps changing their mind about whether they want to be in the relationship, is that really good enough for us? The partner who can never admit to doing anything wrong, is that really good enough for us? The partner who is a nasty drunk, is that really good enough for us? The partner who freezes and shuts down when we cry, is that really good enough for us?

What are the qualities we are looking for? And by qualities I do not necessarily mean how affluent they are or what their Instagram looks like. Perhaps we want someone with a certain degree of emotional literacy who can say how they feel rather than acting it out in a childish way when they are upset? Someone who is able to manage the heightened emotions that we all experience from time to time such as anxiety and anger in a healthy way. Perhaps we want someone who is able to communicate in a non-blaming, non-defensive way?

Once we know the qualities we value, are we able to reject others instead of constantly rejecting ourselves through self-blame or settling? Sometimes people will say, ‘I felt bad saying no to a date with him’ or, ‘she wasn’t really what I was looking for, but I thought I’d give them a try and then I got hooked’. These are all examples of going against our better judgement. We might be worried about hurting the other person. Does that mean that their needs come before ours? No. We all get rejected in various guises, frequently. Whether it be for the job, the promotion, by not winning the lottery. It’s part of life. If someone chooses to get ‘hurt’ by being turned down, then that is up to them.

Or we may say ‘yes’ to individuals even if alarm bells start ringing, for fear we won’t find anyone else. This is a fallacy as there are billions of other individuals out there on the planet. In fact, the longer we stay in something that doesn’t feel right, we lose time with the wrong person when we could be on the path to finding the right person. What keeps us from acting according to our better judgement and instincts, a false belief we adopted about not being good enough. See point 1 on how to challenge this.

7. Your reasons for wanting a partner are flawed

What is behind our desire for a partner? Is it a wish for distraction from a shitty life? Is it a wish to be cared for the way our mum or dad didn't sufficiently care for us? Is it to obtain status or validation? Is it to get security and/or money? Is it to feel more excited and alive? None of these are good enough reasons to seek a partner. If life is shitty, build a new one. If we want status and validation, gain it by doing something meaningful from growing prize tomatoes to winning the Nobel prize. We can find ways to increase our own income if money is important. If we feel numb and depressed, we can find out how we are suppressing ourselves and our emotions in therapy so that we can feel more alive. Or we can take the risk of shaking things up in our life, perhaps re-training, re-locating, moving out of our comfort zone with a hobby, or working less.

If our yearning for a partner is a desire to be cared for, to feel safe or to feel validated, then we need to do some work on re-parenting ourselves. The truth is, even with the ‘perfect’ partner, they will get it wrong sometimes. They will not always be able to read exactly what we need and give it to us when we need it. They will at times be absent or emotionally unavailable or caught up in their own stress. If we place unspoken expectations on our partner to provide what was missing in our parenting, we will often feel disappointed, hurt and missed. We are then more likely to act out in child-like ways, raging or crying or stone-walling or being passive aggressive, which pushes our partner away and then we feel even more hurt.

How do we reparent ourselves? There are the obvious things we read about such as swapping negative self-talk for compassionate self-talk, being kind to ourselves, setting appropriate boundaries, practicing good self-care etc. Sometimes we need a bit more help with this. We need to explore in more detail exactly how our childhood woundsdeveloped and exactly what we need to do in order to mend them. Sometimes we also need to process the wounds so that the hurt is no longer so intense and doesn’t get triggered in unhelpful ways. Psychotherapy which focusses on developmental trauma, such as EMDRor an attachment focussed therapy can really help with this. Only we can heal ourselves, although good therapists and good partners can help with the process. Once we have taken responsibility for our wounded parts, that is when we are more likely to meet the partner of our dreams.

Intrigued to know more about how therapy can help your relationship dynamics? Get in touch and we can talk.

Is The Cost of Therapy Worth It or Just a Rip Off?

When weighing up the cost of therapy, you may find your mouse hesitating to click on the ‘get in touch’ button. You start doing the mental maths of how much it’s going to add up to per month. Then you start thinking about the things you’ll have to go without. Or, you think about all the things you could buy with the money instead. You focus on the monetary cost of therapy and try to decide if it is good value. When making your decision, here are some additional points to consider:

When weighing up the cost of therapy, you may find your mouse hesitating to click on the ‘get in touch’ button. You start doing the mental maths of how much it’s going to add up to per month. Then you start thinking about the things you’ll have to go without. Or, you think about all the things you could buy with the money instead. You focus on the monetary cost of therapy and try to decide if it is good value. When making your decision, here are some additional points to consider:

1. Therapy costs less than divorce

Let’s say I want therapy to stop my marriage from falling apart. My partner has requested I work on anger issues which are creating a tense atmosphere at home. Everyone walks on eggshells around me. The potential cost of not doing therapy is the end of my marriage. This would mean a huge amount of emotional pain and suffering. It might also lead to a costly divorce in which we would both stand to lose the family home. If one year’s worth of therapy works out at around £3000, this is considerably cheaper than the cost of divorce which includes solicitors’ fees and loss of income. Not to mention the heart ache and pain.

2. Therapy leads to more meaningful and better paid jobs

A recent survey showed that a course of therapy leads to an increase in earning. Economists studied data from 2943 men and 5064 women between 1995-2008 to establish the effect of psychotherapy on mental health and income. For men, their income increased by 13%. For women it increased by 8%. If an individual earns £35k and does a year of therapy, they could increase their income to £39,550 which would be 1.5k more than they spent on the therapy.

Why does therapy increase income? Therapy has the means to permanently shift our life onto a higher plane long after the thrill of the new car or tropical holiday fades. If you look back over the last five years at the patterns and habits you have wanted to change, how much have they really changed? For most of us, our everyday busy-ness means we don’t find the time. Or when we’ve got the time, we don’t have the motivation or the discipline to make changes. Months and years can go by like this. Deciding to pay for therapy is securing one hour a week where we can empty out the thoughts going around in our heads, identify what matters and make headway with making those things happen.

Lucia (client’s name and identity has been changed) is an intelligent and talented woman who was doing boring and repetitive work when she first came to therapy. In sessions we explored her interests and what she valued. She became aware of the critical and doubting voices that held her back from pursuing these. In some sessions she experimented with giving voice to more confident parts of her. By the end of the therapy she had found a meaningful career and had doubled her income. She had become more confident and able to speak up and be heard. She also felt more able to handle challenging exchanges and to delegate. In short, she became more employable.

3. Therapy gives you more quality time

We might postpone therapy because we are too busy. But we are too busy doing what exactly? Are we working in a meaningful job where there is a good work/life balance or flogging ourselves to death in a job where we feel devalued and underpaid? Do we come home at night fretting about what our colleagues think of us or whether our boss thinks we are any good? Do we repeat unhelpful relational patterns with colleagues? If so, then does it make sense to prioritise work over therapy? As the well know adage says, if we keep on doing the same old things, we can’t expect anything to change’.

In therapy we create a space to think about our work needs. We explore the activities that feel valuable and meaningful to us. We gain insights into relationships with colleagues and superiors. We learn what we can do differently to make work more enjoyable. We are more able to set healthy boundaries and as a result work is less time-consuming.

Therapy can make us richer not just in monetary terms but more importantly in terms of emotional satisfaction. It leads to improved relationships and finding life more meaningful. Does that mean it’s worth it? That depends on whether you are happy with your life as it is. Are you fulfilled in your profession? Are you in a satisfying relationship or do you keep on repeating the same old patterns? Do you have kind and caring inner talk and practice self-care activities? Do you feel some excitement and joy in your life? Do you regularly make time for fun activities? If the answer to any of these questions is ‘’no’ then therapy can help you with that.

4. Therapy makes you a better partner and parent

I think we can all agree that a happy parent leads to a happy child. A happier parent is one who is in touch with their emotions and able to identify and communicate their needs in an assertive but non-aggressive way to others. A happier parent is one who has worked through any of their own childhood issues that impact on their parenting. A happier parent is one who is able to create enough boundaries so that they have some space in their week where they can pursue interests that are meaningful and fun to them, not necessarily linked to family life. In the same way a happier partner leads to a happier relationship.

Therapy can help us to become more satisfied with our lives. Not necessarily ‘happy’ as this is a temporary and episodic state. However, through therapy we can redress the sources of our unhappiness such as anxiety, depression, poor work/life balance. We do this by becoming more aware of our feelings, our bodies, our needs and our wants. We find ways to articulate these and make changes either actual or through changing our perspective.

So, what are you waiting for? I look forward to welcoming you on the couch ;)

3 Tips to Survive and Thrive in a Killer Work Meeting

“I need a pep talk, girls! I’ve just come out of the worst meeting ever and I’ve got one more to go. It was full of alpha dominants. I was the only voice of reason. Give me some nuggets of wisdom ASAP.” You’ve been there right? Maybe the scenario was a little different but feeling on the backfoot, like you don’t fit in and anxious are the same?I sure have. Or at least I did until these tips…

“I need a pep talk, girls! I’ve just come out of the worst meeting ever and I’ve got one more to go. It was full of alpha dominants. I was the only voice of reason. Give me some nuggets of wisdom ASAP.”

The text pings on my phone. I empathise with how desperate my friend feels in this moment. I imagine her in an elegant Karen Millen trouser suit surrounded by obnoxious individuals hunched around the boardroom table, jabbing their Mont Blancs as they express objectionable views with a healthy dose of afternoon coffee halitosis.

My friend retreats to the lavatory, splashes cold water on her face, wipes away smudged Kohl with toilet paper and dabs lavender essential oil onto her wrists. She stares at her reflection in the mirror as she takes a few breaths, praying for some kind of divine intervention. Then she swivels on her Escada sling backs and heads back to the board room.

You’ve been there right? Maybe the scenario was a little different but feeling on the backfoot, like you don’t fit in and anxious are the same?

I sure have. I’ve sat in big formal meetings finding it harder and harder to get my words out. The less I say, the more I freeze. The worse I feel. Then the self-criticism starts. How can I, a grown woman, who feels at ease chatting with a group of friends sit here like a door mouse? What kind of hypocrite am I? I get frustrated with myself. I feel even worse.

Or at least I did until… these tips.

I propel myself onto the sofa in my tracksuit bottoms and over-sized jumper and dash off an emergency response.

“Yo! You asked for some tips on getting through a killer meeting. Here they are:”

Firstly, think about this fact.

You are not alone. However isolated and outnumbered you feel, you are not alone with this experience. According to Gestalt Group Theory and System Centred Theory (Agazarian, Y), there is no such thing as an isolated experience in a group. Gestalt write Carl Hodges writes:

“whatever comes up for one member ‘internally’ or ‘externally’ emerges from the group…whatever you’re feeling in a group, given the shared ground, chances are that at least one other person is feeling or experiencing something similar. If you ‘voice’ your feeling, issue, difficulty, you may be a voice for a part of the whole.

At least one crisp-shirted alpha-dominant participant was secretly wiping clammy hands. Whether they had the guts to speak up? Now that’s another question. Evidently, they didn’t or you would’ve had their support. But it can be comforting to know you definitely weren’t alone with your thoughts and feelings. And sometimes, when we take the risk of speaking up, we act as leaders. Our courage encourages others and before you know it, you have a sub-set of people all with the same opinion, and you start to have some influence. This is what Yvonne Agazarian, the architect of Systems -Centred therapy calls ‘subgrouping’. Yup, that’s when we start getting the conversation ball back in our court.

Secondly, think on this…. you can empower your mind through your body!

Sensorimotor therapy (Ogden, P and Fisher, J) understands that the body, mind and emotions are connected in a feedback loop. When we experience powerlessness we often feel energetically low and highly anxious. To counter this, you can experiment with lengthening your spine. Try sitting or standing straighter. This helps to regulate the nervous system and balances energy. The movement in our body sends signals to our brain to either energise or calm down. In this way we feel more in control and more able to hold the gaze of the boardroom buffoons. Perhaps with even with a little smile playing at the corner of our tinted cinnamon glossed lips.

Connecting with your core is another Sensorimotor technique. You do this by pulling your tummy in, just like you do in a Pilates class, so you get a nice solid feeling in your middle. Try it now and see how it feels? It shouldn’t’ feel like a work out. But just see what it’s like to lengthen your spine and pull your tummy in. Notice how you feel before you try this and then try it. Once you’ve done it at home you can try it in the meeting for a few seconds. Then relax and notice how you feel in your body and emotionally afterwards. Just doing this as I type this response, I feel more open and uplifted in my chest.

Squaring off your shoulders is something else you can try if you need to match the testosterone fuelled energy in the meeting room. Do this whilst you lengthen your spine, pull in your tummy and take back control!

Thirdly, reframe your experience as a ‘part’ of you.

The feeling of powerlessness in the boardroom doesn’t define you. According to the theory of Structural Dissociation (Van der Hart et al), we all have different parts or aspects of us. How we act at work differs from how we are with a partner or with friends. Reframing your powerlessness as a ‘part’ that gets triggered helps you to feel less out of control.

Then ask, “what does this part need to feel better?” You can imagine it as a younger part of you. Does it need to feel strong? Does it need to feel like it belongs? Does it need to feel safe?

Let’s say my triggered part feels powerless. I remember a time when I felt influential. I gave a speech at my university graduation and audience members came up afterwards, eager to get to know me.

Using a technique from EMDR therapy (Shapiro, F), bring this positive memory to mind as vividly as possible. If it’s an image of a family gathering, imagine the room, the smells, the tastes and the quality of the light. Notice where you feel the good feeling in your body. When it’s strong you can tap alternately on one knee and then the other up to 15 times. You can repeat this 3 to 5 times.

The bi-lateral stimulation reinforces the neural networks connected to power. Visualising activates them and tapping helps to strengthen them. A bit like adding extra voltage to the lights on the Christmas tree so the glow brighter.

But what if I’ve never felt powerful? That doesn’t matter. Can you think of someone else? It can be either a person you know or someone you don’t know at all like Barack Obama or Angela Merkel. Then carry on with the visualisation as above.

Once you’ve tapped this image in, you can bring it to mind before the meeting. Or even in the middle of the meeting for a second or two. Don’t worry, you don’t need to tap after the first time! Although tapping in itself activates the parasympathetic nervous system and some of my clients confess to using it in meetings!

If things get critical, what’s to stop you popping to the restroom and recalling the resource image as you lengthen your spine and pull in your core?

There you have it, three tips to nail that killer meeting. Make sure to try them in the spirit of ‘experimenting’ and not something you can get wrong. Even getting a bit of relief is positive and the more you do it, the easier it gets.

Go get ‘em, girlfriend! Relish the moment when all eyes are shining on you with respect and admiration. Enjoy the warm, uplifting yet calm feeling inside as you realise you’ve just nailed-that-meeting-once-and-for-all!

Oh, and don’t forget to let me know how it went. Nothing like sharing in on a bit of schadenfreude ;)

References

Agazarian, Y, M (2006), “ Systems- Centered Practice”, Karnac, London.

Hodges C. (2003), “Creative processes in Gestalt group therapy”, in Spagnuolo Lobb M., Amendt-Lyon N. (eds.), Creative license: the art of Gestalt therapy, New York, Springer.

Ogden, P and Fisher, J, (2015), “Sensorimotor Psychotherapy”, New York, Norton.

Shapiro, F (2001), Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing: Basic Principles, Protocols, and Procedures. New York, Guildford Press.

Van der Hart, Nijenhuis & Steele, (2006) “The Haunted Self: Structural Dissociation and the Treatment of Chronic Traumatisation. New York, Norton.

How to Save the Relationship - 3 Critical Changes to Make Before It's Too Late

The start of the relationship feels like a meeting of kindred spirits. The other person ticks many of the boxes that had been left unticked in the past. They “get” us. They share our values. They care. They understand our quirks. They even have similar quirks. We feel like best friends and lovers. They are interested in us as and not just as a sex object. But the sex is intense. A dream gets ignited. A hope of a happy future with this person is born.

First published and edited by Elephant Journal.

“How will I know if he really loves me?”

The late Whitney Houston sings in the background. The couple is looking at the floor, glum and stuck. They’ve been in the same situation of “not knowing” for two years. The relationship is not moving forward and yet neither of them want to break up. The same cycle plays out like a broken record, a relationship punctuated by regular dramas. Each blow up resets it to zero. They have split up and got back together more times than they can remember. It’s a tiring dance that can’t last much longer.

Been in this situation? I have, as have many of the clients I’ve worked with.

The start of the relationship feels like a meeting of kindred spirits. The other person ticks many of the boxes that had been left unticked in the past. They “get” us. They share our values. They care. They understand our quirks. They even have similar quirks. We feel like best friends and lovers. They are interested in us as and not just as a sex object. But the sex is intense. A dream gets ignited. A hope of a happy future with this person is born.

Then, the disharmony starts.

We see parts of them that don’t fit the person we fell in love with. We feel stunned, disenchanted, repelled. So, we walk away and feel unbearably sad. We talk to them in our heads. We miss them when we do new things. We revisit the relationship. That hope or dream is still alive and burning in our hearts.

We try again. And it happens again. And again. And again. Each time, we gather more evidence for why the other person is the “bad guy.” We stockpile this “evidence” to make a case for why we can’t commit to the relationship fully. We say, “If only he/she would sort out their issues then this relationship would improve.” Yet we don’t leave because we still hope, we still dream, and beneath all the disharmony, we still love. The relationship sways back and forth like a swing in a deserted playground.

Smell the coffee.

When we are only willing to commit if the other person changes, then things will never improve. Individuals attach different meanings to the word “commitment,” but essentially, it’s about saying “yes” to the relationship and deciding to step on board with both feet.

We shift from focussing on what they are doing wrong and look at the part we play. As Gestalt therapist Robert Resnick says, “relationships are co-created.” We are 100 percent responsible for our part and how we react to our partner’s “flawed behaviour.” We play our part in the dynamic. We defend, we blame, we withdraw, we meet for coffee, and then we play again. Since a relationship is a system, any small change will inevitably change the entire system.

Snakes and Ladders is a board game, not a relationship.

When we only engage conditionally, then, we keep the relationship suspended and uncertain. These are hardly the right conditions for either of us to take an honest look at ourselves and be open to behaving differently. It’s like a parent telling their child who is struggling at school that if she gets good grades then they will love her. She will most likely become so anxious that she sabotages her own success.

Feeling motivated to do better comes from standing on firm ground. When we are anxious about the security of the relationship and whether the other is “in” or “out,” we don’t feel safe enough to focus on what we bring to the table. But we try nevertheless. Then we stumble and we get told, “There you go, I told you so, you just can’t help your bad character.”

We start to attack and defend. The pendulum swings. When we are more “in,” the other is more “out.” When the other is more “out,” we are more “in.” We are never on the same page at the same time. With each incidence, we hurtle back down the ladder and start at zero. But still, we stay. And things stay the same. Up and down and a merry-go-round. We are stuck.

Just step in.

Gestalt Therapy theory talks of polarities. Think yin and yang, day and night. Where one behaviour exists, the polarity also exists. Within a shy person, there is an extrovert. Within a compliant person, there is a bossy person. When we don’t acknowledge both polarities, then we behave in an unbalanced way. Relationships also have polarity behaviours. What’s the opposite of staying on the fence? You got it—commitment!

…And commit.

Committing means no more conditions and blame. It means stopping the dance of pursuing, distancing, and showing up naked in the ring in front of the other. It means closing the exits and giving the relationship a chance to thrive. It means seeing disharmony as something to overcome and learn from—not as an excuse to exit.

It means deciding to not play the same old relational record on repeat. It’s tiring, confusing, demoralising, and clearly not working. It means addressing our “madness” and how the other triggers that in us.

Still scared? Deal with it!

We feel cautious. Can we trust the other? What if we go for it and it doesn’t work out? As Gestalt Therapy theory says, “whenever we take the risk of doing things differently we feel anxious.” It can’t be helped. It’s part of life. We can only avoid uncertainty and anxiety if we die.

Stop looking for perfection because you won’t find it. We work on accepting that our partner is a flawed human being, just as we are. Stop looking for your soulmate, because you wouldn’t know them if they were jumping up and down naked in front of you.

Philosopher Alain de Botton, in his refreshing and down-to-earth The Course of Love, discusses the concept of the soulmate, which arose with the romanticism period of European history. Until then, families chose matches that were mutually beneficial. We are supposed to recognise our soulmate instantly. We search high and low for that special person that feels “just right.” But as de Botton says,

“None of this has anything yet to do with a love story. Love stories begin…not when they have every opportunity to run away, but when they have exchanged solemn vows promising to hold us, and be held captive by us, for life.”

Chemistry is for the school science lab.

Dr. Young, who devised Schema Therapy, says that strong chemistry with someone can be a warning sign that we are attracted because they are similar to the parents that wounded us. For example, the woman abandoned by her father who chooses unavailable men. Or the man with the depressed mother who falls in love with a depressive.

The relationship won’t reveal itself like a flower growing in shit. You need to do the work. Rake the shit and prepare the ground.

Here’s how:

1. Stop blaming and criticising.

Psychotherapist Susan Anderson has coined the term “outer child,” which is the part of us that blames and criticises the other. The part that sabotages relationships. Similarly, schema therapy describes the “angry child” mode. We all have one. It directs itself at us as and tells us we are crap. We can start to become aware of it, even track it. We can also monitor the amount of blaming and critical thoughts we have toward our partner, and balance them out by thinking about what we like about our partner.

2. Stop defending.

We can stop defending ourselves so readily. Sometimes, we can’t admit to stuff because we believe (deep down) that to do so makes us a bad person. We will do anything to defend ourselves from the shame, which comes from a negative core belief. We might believe that “making a mistake” or “being imperfect” makes us a bad, defective, and flawed person.

Conversely, if my self-worth is not attached to my behaviour then I can say, “You’re right, I’m sorry for taking out my bad mood on you.” I still feel confident that I’m a good and lovable person. If acknowledging blame means I am now an awful, despicable, condemned person then, of course, I will defend myself like my life depends on it.

Unfortunately, many of us were parented in ways that fostered shame. Gestalt Therapist Robert Lee conducted a study on the internalised shame on marital intimacy. He found that couples with high internalised shame scored low in both marital intimacy and marital satisfaction. So, start challenging those negative core beliefs and believe you are entirely worthy and acceptable.

3. Ditch the ‘”if” and stay with the “now.”

In the heat of the moment when the other triggers us and we feel intense anger, anxiety, jealousy, or whatever else, we can use the mindfulness technique of embracing the feelings without acting on them.

You might need to take some space in order to do so. I don’t mean leave the relationship though! Tara Brach, psychotherapist and mindfulness teacher, has a great technique called the “Yes” meditation. Rather than resisting everything that is “wrong” we embrace it.

If I’ve had a spat with my partner, I distance myself physically, close my eyes, and focus on my feelings and body sensations. Firstly, I notice everything I don’t like. I don’t like what they have said. I don’t like that they have “triggered” me. I don’t like that I have fallen for the trigger. I don’t like that I got angry. I don’t like the whole situation, in fact, I hate it. I’ve had enough! And then I practice saying “yes” to every element I don’t like. I notice there is more space and I uncover a tender spot in my heart. My feelings become less intense and I can reflect in a more balanced way on how I want to respond to the situation.